Building a Terminal-Based Music Sequencer in Python

Why a Terminal Sequencer?

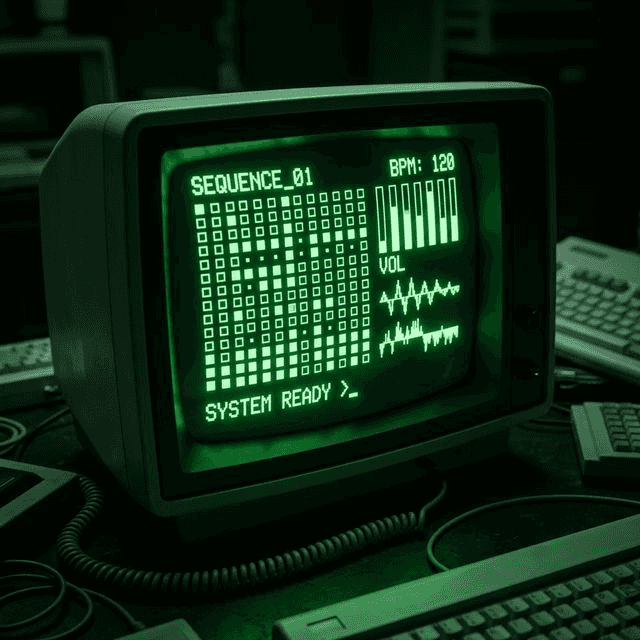

In a world of sleek DAWs (Digital Audio Workstations) like Ableton and Logic Pro, there’s something charming about going back to basics. I wanted to build a music tool that felt like it belonged in a hacker’s toolkit—something fast, keyboard-driven, and purely text-based.

Thus, the Python TUI Sequencer was born. It’s a 16-step sequencer that runs entirely in your terminal, featuring real-time synthesis, sample playback, and a fully navigable interface.

The Stack

- Python 3: The core language.

- Curses: For drawing the TUI (Terminal User Interface).

- PyAudio: For low-latency audio streaming.

- NumPy: To generate waveforms and process DSP effects efficiently.

The Interface: Taming Curses

Building a UI in the terminal means using curses. It’s powerful but tricky. You have to handle every keypress, redraw the screen manually, and ensure that your UI loop doesn’t block your audio loop.

I settled on two main views:

- Sequencer View: A classic 16-step grid where you place notes for Kick, Snare, and Synths.

- Mixer View: A control panel to adjust volume, effects (Echo, Tremolo), and waveform types.

The challenge? State synchronization. The TUI runs in the main thread, while the audio engine runs in a background daemon thread. They both read from a shared Settings object, so I had to ensure that changing a note in the UI instantly reflected in the next audio loop without race conditions.

The Audio Engine: From sox to PyAudio

Initially, I tried shelling out to sox commands for every beat. It was a disaster. Spawning 5-6 processes every 125ms caused massive CPU spikes and audible stuttering.

The solution was a Persistent Audio Engine.

I wrote a custom AudioEngine class using PyAudio. Instead of spawning processes, it opens a single audio stream and keeps it open. A background thread constantly feeds this stream with audio buffers.

# Simplified Audio Loop

def _audio_loop(self):

while self.running:

# Check if we have audio in the buffer

if len(self.audio_buffer) >= self.buffer_size:

chunk = self.audio_buffer[:self.buffer_size]

self.stream.write(chunk)This reduced latency to near-zero and dropped CPU usage significantly.

DSP: Writing Effects in Python

With direct access to the audio buffer (as NumPy arrays), I could write custom DSP (Digital Signal Processing) effects from scratch.

The Echo Effect

An echo is fundamentally just adding a delayed, quieter version of the signal back into itself.

def apply_echo(audio, delay_ms, decay):

# Calculate how many samples back the delay is

delay_samples = int((delay_ms / 1000.0) * sample_rate)

# ... create output array ...

# Add the delayed signal

output[delay_samples:] += audio[:-delay_samples] * decay

return outputI also implemented Tremolo (amplitude modulation) and Pitch Shifting (via resampling).

Persistence

Finally, a tool isn’t useful if you can’t save your work. I used a simple JSON structure to save the state of the sequencer. The trick was handling the difference between “saved state” and “runtime state” (like which track is currently muted or soloed), which shouldn’t necessarily be saved to disk permanently.

Conclusion

This project was a deep dive into the intersection of art and code. Building a sequencer taught me about thread management, audio buffering, and the timeless utility of TUI applications.

If you want to jam in your terminal, check out the code!

References

About the author

Written by Nicholas Diesslin Pizza acrobat 🍕, typographer, gardener, bicyclist, juggler, senior developer, web designer, all around whittler of the web.

Follow Nick on Twitter!